Well, it was bound to happen sometime. Four movies into the Underworld series, I finally broke down and saw one of the things in theaters. It was back in February when I was joined by three other gentlemen for a 5:10 showing of the 3-D version of Underworld: Awakening (for some reason the 2-D version wasn’t showing at all in my town), and it’s pretty safe to say we all got precisely the movie we were expecting. (more…)

Category: Reviews

Sometimes we get asked to share our opinions. Sometimes we don’t get asked but share them anyway.

Full Moon Features: Witnessing the Rise of the Lycans

Every three years — almost like clockwork, it seems — we get another installment in the Underworld series. (Which I guess means we’re in for Underworld: Here Comes Another One come January 2015.) Keeping to that schedule, the first month of 2009 brought us a prequel, Underworld: Rise of the Lycans, which temporarily set aside the present-day storyline in order to delve into the past to explore where the whole Vampire/Lycan war began.

Every three years — almost like clockwork, it seems — we get another installment in the Underworld series. (Which I guess means we’re in for Underworld: Here Comes Another One come January 2015.) Keeping to that schedule, the first month of 2009 brought us a prequel, Underworld: Rise of the Lycans, which temporarily set aside the present-day storyline in order to delve into the past to explore where the whole Vampire/Lycan war began.

Directed by Patrick Tatopoulos, who designed the creatures for all three films, and based on a story and screenplay that was the work of no less than five writers (including original director Len Wiseman and screenwriter Danny McBride), Rise of the Lycans tells how, well, the Lycans rose up against their vampire masters way back in the mists of time. It also doubles as the origin story for Lucian (Michael Sheen), the first Lycan, i.e. a werewolf who is able to take human form. (Much is made of the distinction between pure-blood werewolves, who are little more than savage beasts, and Lycans, who can be controlled and enslaved.)

Raised from birth by vampire leader Bill Nighy, Sheen grows up alongside Nighy’s daughter, who grows up to be the headstrong Rhona Mitra (and, not incidentally, his lover). Of course, this raises certain questions that the movie never pauses to consider. For instance, do vampire and werewolf children simply grow to a certain age and then stop? How does an immortal actually reach the point where they look middle-aged like Nighy or the other members of the vampire council? And furthermore, why am I bothered by these things if the people behind the series seemingly aren’t?

Anyway, also returning from previous installments are the impossibly deep-voiced Kevin Grevioux, who we first encounter as a human slave, and Steven Mackintosh, the vampire historian from the second film that I had completely forgotten about until I looked him up on Wikipedia. And I was happy to note that Paul Haslinger, formerly of Tangerine Dream, was brought back to provide the music. (He had scored the original Underworld but was apparently unavailable to perform those duties for Evolution.) That just leaves Kate Beckinsale out of the loop, since the events in the story take place long before she was turned (although she does provide the narration that opens the film and appears at the end courtesy of recycled footage from the first film).

Lest you think my goal is to bash this series in toto, I will say that Rise of the Lycans surprised me by being much better than I thought it would be. In fact, I’m prepared to go so far as to call it the best film in the series, which is saying something when you consider it’s basically a feature-length expansion of one of the flashbacks from the first film. And this is also in spite of the preponderance of pretentious dialogue and the monotonous blue light that every scene in bathed in, both of which are part and parcel of every Underworld movie. Some things you just can’t get away from. At least this installment, by virtue of its period settling, was able to do without all the tedious gun fights. Too bad they would be back with a vengeance when the time came to reawaken Kate Beckinsale and see if she could still fit into her shiny, black catsuit…

Live-Tweeted Quasi-Review of “Anathema”, the Lesbian Werewolf Horror Darling of Kickstarter

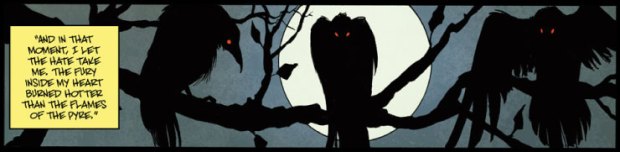

In July 2011 I posted about one of the first Kickstarter projects I ever contributed to: Anathema. The goal was to fund the illustration, colouring and printing of issue #1 of a werewolf comic that writer Rachel Deering called “a return to classic horror in comics”. Now, seven months after that post, and five months after the project surpassed its Kickstarter goal, the first issue of Anathema is circulating among Kickstarter contributors. I got my claws on a PDF and sat down to read it yesterday, during a break at work.

I’m going to leave the formal analysis of Anathema to people who actually know how to review comics – I’m just a werewolf fan with a blog. Instead, because I’m a silly git, I decided to live-tweet my reading, making (spoiler-free) comments on every page of the book. I’ve reproduced those tweets in chronological orders, and I’m going to let this stand as my formal review of the book.

Time to read @racheldeering‘s Anathema! Even the intro on the inside of the front cover gave me chills.

I’m gonna live-tweet this reading, page by page, omitting spoilers. Page one: okay, dad’s a dick. Lovely colours, though.

Page 2: Authentic emotional response to characters I just met. Great panel layout. Dad’s going to need some Bactine!

Page 3: First overtly supernatural incident. Intense but not too dramatic. Love the time-shifted narration. That’s flame-resistant hair!

Page 4: Third segment of this page expresses her isolation perfectly. Well done Chris Mooneyham.

Page 5: I want to live in Henrich’s house and visit his manicurist.

Page 6: Jeez, what a drama queen.

Page 7: UGH that TONGUE. Put it away, dude!

Page 8: Great colours and lines. Any of these panels could be posters. Nice work explaining the crows, too.

Page 9: Any of these could be levels in a Zelda game that I would play the fuck out of.

Page 10: Great character design. Brilliant work to tie the plague doctor’s mask concept into the design. The glow around the moon!

Page 11: Come on, Henrich, give up the goods. Also, you look like Christopher Lloyd. This is not a bad thing.

Page 12: Where can I get me some of those?

Page 13: Come on, at least freshen the linen. Nice transition out of the scene.

Page 14: I probably shouldn’t be reading this at work.

Page 15: When Anathema gets made into a movie (as it inevitably must), this’ll make a great little nasty sequence.

Page 16: Part of me is disappointed that there’s no “It’s dangerous to go alone! Take this.” moment.

Page 16 cont’d: I’m impressed with how solid these characters are. Henrich could’ve been a 2-D quest-giver, but he’s richer than that.

Page 17: Holy fuck, lady, where’s your climbing gear!?

PP 18-19: BAD. ASS. A lot of werewolf fanboys (and a few werewolf fangirls) are going to pin this spread over their beds.

Page 20: Immediate thoughts: this would be a great video game, either 1st-person slasher or 2D side-scroller. I like that she mentions pain.

Page 21: PRIMAL. “As I, myself, become the object of fear.” This is exactly what I love about horror and werewolves.

Page 22 / last page: Great setup for the next issue. This isn’t a cliffhanger, this is a gun, loaded and cocked.

So, yeah. Verdict on Anathema, issue 1? Basically, you need to buy this thing as soon as you can, and then we need to fund the other issues.

Go follow @racheldeering and pester her to sell you a copy – she’ll have some pretty soon, I think. DAMN, I’m all riled up!

So, while that wasn’t a proper review, over the course of 25 tweets, I exclaimed over the quality of the writing, the art, the colours, the characters and the layout (and, come to think of it, I meant to mention the lettering too). I also said that Anathema would make a great film or video game, and although I didn’t tweet about it, I pitched a little fit when I got to the last page because it’s over and I need more. The book was a terrific effort by writer/letterer Deering, artist Chris Mooneyham and colourist Fares Maese, and I think Kickstarter contributors (and fans of horror comics in general) are going to love it.

I want to take a second to expand on my comment about page 21: This is exactly what I love about horror and werewolves. The “this” I’m referring to is the vicarious indulgence of a particular blend of righteous fury and macabre glee that I think horror fans (and most people in general) are familiar with, even if they don’t want to admit it. Articulated as a thought, it might go something like “I want to do terrible things to people who deserve it, and suffer no repercussions.” Act so in real life and at best you’d be a sociopathic asshole, but channel that desire into a fictional vessel like Anathema’s grieving anitheroine (or the miserable little brother from The Wrong Night In Texas) and you’ve got werewolf therapy – a wonderful outlet for a very dark but very human urge. This is one of the things I’ve always loved about werewolves, and although not every werewolf story manages it, Anathema delivers.

So. Er. If that sort of thing sounds good to you, or if you just want to read an awesome werewolf comic where a lady fights werewolf-style for the soul of her murdered lover, watch Rachel Deering’s Twitter profile for Anathema issue #1!

Web Series “Wolfpack of Reseda”: Drink some True Blood while driving your Kia to your job at Initech

According to the end of the first episode of Wolfpack of Reseda, when you’re infected with lycanthropy you immediately receive enormous feathery sideburns and a brand new Kia Soul. (more…)

Full Moon Features: The Underworld series, Part One

He’s a life-saving surgeon, she’s a death-dealing vampire — can the two of them get along? That’s the big question posed by 2003’s Underworld. (Actually, that’s not strictly true. The real question the filmmakers probably posed was “Hey, wouldn’t it be really cool if we made a movie where vampires and werewolves fought each other with guns while there was a Romeo and Juliet thing going on?”) I gave Underworld a wide berth when it was first released nearly a decade ago, largely because the trailers I saw were chock full of CGI werewolves (my favorite kind, don’tcha know), but I finally gave in and watched it a few years later just so I could get it under my belt. (This is how I wind up watching a lot of crappy werewolf movies, and I do mean a lot.)

He’s a life-saving surgeon, she’s a death-dealing vampire — can the two of them get along? That’s the big question posed by 2003’s Underworld. (Actually, that’s not strictly true. The real question the filmmakers probably posed was “Hey, wouldn’t it be really cool if we made a movie where vampires and werewolves fought each other with guns while there was a Romeo and Juliet thing going on?”) I gave Underworld a wide berth when it was first released nearly a decade ago, largely because the trailers I saw were chock full of CGI werewolves (my favorite kind, don’tcha know), but I finally gave in and watched it a few years later just so I could get it under my belt. (This is how I wind up watching a lot of crappy werewolf movies, and I do mean a lot.)

I realize I may be in the minority around these parts, but I’m just not that big on the Underworld franchise, which I feel squanders a theoretically unsquanderable premise by getting bogged down in its monochromatic visual palate, humorless characters, and the convoluted mythology that original director Len Wiseman cooked up with screenwriter Danny McBride and actor Kevin Grevioux. (For the record, I have a similar problem with both the UK and North American editions of Being Human, which have their moments, to be sure, but are never allowed to be as fun as a show about a vampire, a werewolf and a ghost living under the same roof should be.)

If the first Underworld movie accomplished nothing else, it introduced the world to Kate Beckinsale’s vampiric, gun-toting, catsuit-wearing Death Dealer (which is their fancy term for werewolf-killer), who becomes attached to human Scott Speedman even after he’s been bitten by a Lycan and thus fated to become one at the next full moon. The next full moon, incidentally, just so happens to coincide with The Awakening, when the vampire elite is gathering to bring one of their elders out of hibernation. In the meantime, the vampires lounge about in their mansion acting all decadent while the werewolves skulk around their underground lair playing Fight Club. When you get right down to it, the vampire/werewolf war is a class struggle on par with the Autobots vs. the Decepticons — just don’t expect me to watch Transformers anytime soon to back that up.

Anyway, I haven’t gotten to the plot yet and there sure is a lot of it. In addition to The Awakening, there’s a lot of intrigue surrounding the collusion between the leaders of the two factions, which Beckinsdale attempts to bring to light by waking vampire elder Bill Nighy a century ahead of schedule. And it turns out Speedman is the key to bridging the gap between the two races, but some people would rather see that not happen, hence all the gun battles and people throwing each other around in decrepit subterranean chambers. One has to wonder, though, whether the decision to allow the vampires in the film to be seen in mirrors was made so the filmmakers could stage the final epic battle in a large pool of water without having to worry about erasing the vampires’ reflections. Oh, yes. And what tactical advantage is there to the werewolves charging their enemies sideways on the walls? Did the filmmakers go with that simply because it looked cool? My guess would be a resounding yes.

Well, enough people got suckered into seeing the first Underworld that a sequel was inevitable, and 2006’s Underworld: Evolution was the result. The question was, had the Underworld series evolved in the intervening years? Ehh, yes and no. After a prologue set in 1202 A.D. (in which we find out that all vampires and werewolves are descended from twin brothers who were bitten by a bat and a wolf, respectively), we return to modern day where professional ass-kicker Beckinsale is on the run after having killed elder Nighy, with vampire/werewolf hybrid Speedman trotting along beside her. He’s still new to the whole “needing blood to survive” game, but there’s little time to dwell on that with supervampire Marcus (Tony Curran), who was awakened at the end of the first film, on the loose.

Once again directed by Len Wiseman from a screenplay by Danny McBride, Evolution ups the gore factor somewhat and, like the first film, shows a disappointing predilection for characters shooting each other with heavy weaponry (except, of course, for the prologue, where the vampires ride in on horseback and hack and slash at their hairy foes with swords and axes). There’s also an emphasis on cutting-edge technology, particularly in the scenes with Sir Derek Jacobi as an immortal who has been cleaning up the messes left by his progeny over the centuries. One thing that’s thankfully kept to a minimum, though, is the posturing that marred much of the dialogue in the first film, where it seemed like every other scene somebody was ordering somebody else to “Leave us.” Alas, that would return to a degree in the prequel, which expands a five-minute flashback from the first film to feature length, but that’s a story that will have to keep for another month.

Full Moon Features: Joe Johnston’s The Wolfman, two years later

It’s tantalizing to think about The Wolfman that might have been. Mark Romanek’s music videos are so distinctive that it’s pretty much a guarantee that his treatment of the material would have been, too. Just take a gander at “Closer” or “The Perfect Drug” by Nine Inch Nails, or Johnny Cash’s “Hurt” or even Michael & Janet Jackson’s “Scream” and you’ll see what I mean. The man knows his way around striking — and frequently disturbing — imagery.

It’s tantalizing to think about The Wolfman that might have been. Mark Romanek’s music videos are so distinctive that it’s pretty much a guarantee that his treatment of the material would have been, too. Just take a gander at “Closer” or “The Perfect Drug” by Nine Inch Nails, or Johnny Cash’s “Hurt” or even Michael & Janet Jackson’s “Scream” and you’ll see what I mean. The man knows his way around striking — and frequently disturbing — imagery.

Once slated to be his follow-up to the well-regarded One Hour Photo (which starred the hirsute Robin Williams — how is it possible that he never made a werewolf movie? Or did his nude scenes in The Fisher King render that redundant?), Romanek’s Wolfman was scuttled when the director reached an impasse with Universal over the budget. Which is ironic considering the way it swelled from $100 to $150 million thanks to all the reshoots and retooling the film underwent after it wound up in the hands of Joe Johnston, whose experience with special effects-driven films made him, if not ideal, at least a suitable replacement. (I don’t even want to contemplate what a Brett Ratner-helmed Wolfman would have looked like.)

Even with a steady hand at the tiller, Universal did little to inspire confidence when, barely a month into principal photography, The Wolfman‘s release date was bumped from February to April 2009. Not that much of a leap, really, but that wasn’t the first time it had been pushed back. After all, the film had originally been scheduled for a November 2008 release and, in fact, would get punted around the studio’s slate several more times before ultimately landing on Valentine’s Day weekend, 2010. This put it in direct competition with the romantic comedy Valentine’s Day, which may have seemed like shrewd counter-programming on paper, but wound up hobbling its commercial prospects (which, to be perfectly frank, weren’t helped by the critical pummeling the film received once it finally limped into theaters).

One thing that definitely didn’t help matters was the decision to cut out a sizable chunk of the first hour in order to get to Lawrence Talbot’s first transformation that much sooner. Not only did this destroy the flow of the story (and completely drop Max von Sydow’s cameo as the man who gives Talbot his silver wolf’s head cane), it also inspired the studio to scrap Danny Elfman’s already-recorded orchestral score and substitute an electronic one by Paul Haslinger, which he composed in the style of his work on the Underworld series. When that proved to be a bad fit they went back to Elfman’s music, but the job of reshaping it to fit the studio cut had to be left to others since Elfman had other commitments.

When I think of how The Wolfman turned out, I can’t help but wonder how it would have fared with critics and audiences if Universal had released Johnston’s cut to theaters instead of the version they allowed to be test-marketed to death. I know when I finally got to see the director’s cut months later on DVD, I thought it was such a marked improvement across the board that even some of the things that rankled me when I saw it in theaters — like all the CGI and quick cuts in the action sequences — didn’t bother me so much the third time around. (And yes, this does means I saw it twice on the big screen. I was lucky it hung around until the end of the month so I could see it at the next full moon.)

I won’t enumerate all of the differences between the two versions, but I did like the extension of the opening sequence and that we got to see Benicio Del Toro on stage briefly. (In the theatrical cut, we had to take it on faith that he was a renowned Shakespearean actor.) And Emily Blunt coming to see him at the theater was a much stronger choice than simply having her write him a letter telling him about his missing brother. There’s also more about his gypsy mother and the villagers’ superstitious nature and so forth. As far as I’m concerned, there’s no question that these cuts were harmful to the film. Sure, an hour of screen time elapses before del Toro wolfs out, but in the director’s cut the first half of the film no longer feels rushed and the second half doesn’t seem so lumpy and misshapen. Maybe if it had been left alone, the film would have done well enough at the box office to merit a direct sequel following Hugo Weaving’s Inspector Aberline as he comes to terms with his own lycanthropy problem (a prospect clearly set up in the film’s closing moments). As it is, we’re left with the reboot Universal supposedly has in the works. If only they’d gone to the trouble of getting the first film right, that wouldn’t have been necessary.

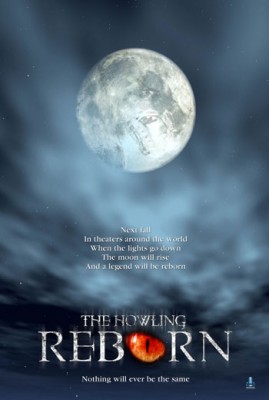

Full Moon Features: The “Rebirth” of The Howling series

After Howling: New Moon Rising limped into video stores in 1995, the long-running series was finally put out of its — and our — misery. Seven films in, any connection with Gary Brandner’s original novels had long since been severed and it couldn’t be denied that the bad films in the franchise easily outstripped the good ones. Short of sending its werewolves into space (an idea that I’ve seen in comic form, but never on the silver screen), everything that could be done with them, had been done with them. Well, I guess there was one more place they could be sent: high school. However, that would have to wait until after the emergence of Twilight and the teen supernatural romance cottage industry it inspired. Only then was the time right for The Howling to be, ahem, Reborn.

After Howling: New Moon Rising limped into video stores in 1995, the long-running series was finally put out of its — and our — misery. Seven films in, any connection with Gary Brandner’s original novels had long since been severed and it couldn’t be denied that the bad films in the franchise easily outstripped the good ones. Short of sending its werewolves into space (an idea that I’ve seen in comic form, but never on the silver screen), everything that could be done with them, had been done with them. Well, I guess there was one more place they could be sent: high school. However, that would have to wait until after the emergence of Twilight and the teen supernatural romance cottage industry it inspired. Only then was the time right for The Howling to be, ahem, Reborn.

Based, at least according to the credits, on The Howling II by Brandner (a book I haven’t read, so I can neither confirm nor refute this claim), The Howling: Reborn was co-written and directed by Joe Nimziki (whose only previous directing credit is on an episode of The Outer Limits from 1997), who opens on a scene of a very pregnant artist (Ivana Milicevic) who’s stalked through the streets of an unnamed city by a growling P.O.V. camera and, once she reaches her studio, presumably slashed to death by something with big claws that apparently wants to get at what’s in her belly. Well, the clawed thing (what could it be?) doesn’t succeed because 18 years later it has grown up to be gawky high school senior Landon Liboiron, our humble narrator. Or maybe it did because after he reaches his 18th birthday, Liboiron begins exhibiting all the usual signs of lycanthropy — improved vision (which he discovers while texting in class), fast healing, incredible strength and agility, and a sudden change in diet from being a strict vegetarian to craving meat. It’s too bad all this happens to him right before graduation. He could have really tore it up on the lacrosse team.

Having taken in an entire season of MTV’s Teen Wolf last year, it didn’t surprise me when the supporting cast slotted into their predestined roles. There’s the main character’s geeky, wisecracking best friend (Jesse Rath), the girl he has a terrible crush on and, once he’s turned, has to control himself around (Lindsey Shaw), and the rich jock who makes our hero’s life a living hell for no good reason (Niels Schneider). The only one who doesn’t fit is Liboiron’s father (Frank Schorpion), who’s known about his condition from birth and has done all he can to keep it in check. Then a mystery woman shows up, but if I tell you who she’s played by (hint: it’s Milicevic), her true identity shouldn’t be too hard to guess. Then again, she’s able to pull the wool over Schorpion’s eyes until after she’s gotten him drunk and tied him to his bed — a scene crosscut with Shaw tying Liboiron up when she catches him looking up a book on lycanthropy in the school library. I guess father and son both have a thing for light bondage. Must be genetic.

Anyway, I’m skipping over huge swaths of the plot (I haven’t even mentioned the graduation party where Liboiron is drugged and where he catches sight of his first werewolf, or his bathroom fight with Schneider, who turns out to be packing heat, or the sad birthday party where a morose Schorpion gives his silver wedding band to Liboiron, or the awkward exit interview with his principal where he’s berated for being on the debating team that only took home the silver trophy — because we know that isn’t going to come in handy later on), but the whole shebang climaxes on graduation day, which just so happens to coincide with a “very rare” blue moon, when packs of werewolves all over the world plan to rise up and take over. On the local level, this means Liboiron has to give in to his bestial tendencies and when he finally transforms — an unimpressive computer-assisted effect that comes a full hour after his first reluctant utterance of the w-word — it’s so he can have a knock-down, drag-out, wall-busting battle royal with the alpha werewolf. Because if there’s anything The Wolfman taught us, it’s that audiences crave werewolf wrestling, especially when the camera’s so shaky and the lights are so low that you can’t see what’s going on. Frankly, I don’t know if I believe the filmmakers’ claim that “No actual werewolves were harmed in the making of this motion picture.” I totally saw them whaling on each other. That must have at least caused some bruising.

Book Review: “Werewolves – An Illustrated Journal of Transformation” by Paul Jessup

Werewolves – An Illustrated Journal of Transformation is the tale of Alice, a young woman who gets attacked by a pack of wolf-like creatures and then documents her changes (and those of her brother Mark, who was attacked too) over three weeks with journal entries and evocative illustrations. Writer Paul Jessup and artist Allyson Haller have created a teenaged femme werewolf tale that stands shoulder to shaggy shoulder with Ginger Snaps.

It seems like there a lot of ways a journal-style project like this could go wrong: clumsy narrative info-dumps, poor pacing, inauthentic voice, incidental or uninteresting illustrations. Werewolves suffers from none of these problems. The events we expect to read about – the attack, the mysterious symptoms, the strange people following her and wooing her brother – are detailed but not belaboured. Alice is clearly frightened but there’s no overwrought hand-wringing or dire pronouncements. The entries do a wonderful job of conveying Alice’s emotions and the increasing tension and danger of the story – but there’s also a melancholy sort of sweetness, too, and a real sense of sisterly concern when she writes about Mark. The writing is intimate without feeling voyeuristic, which is quite a feat considering we’re reading a teenager’s private thoughts.

It seems like there a lot of ways a journal-style project like this could go wrong: clumsy narrative info-dumps, poor pacing, inauthentic voice, incidental or uninteresting illustrations. Werewolves suffers from none of these problems. The events we expect to read about – the attack, the mysterious symptoms, the strange people following her and wooing her brother – are detailed but not belaboured. Alice is clearly frightened but there’s no overwrought hand-wringing or dire pronouncements. The entries do a wonderful job of conveying Alice’s emotions and the increasing tension and danger of the story – but there’s also a melancholy sort of sweetness, too, and a real sense of sisterly concern when she writes about Mark. The writing is intimate without feeling voyeuristic, which is quite a feat considering we’re reading a teenager’s private thoughts.

The text in Werewolves is balanced out with an abundance of beautiful illustrations, rendered in what looks like graphite and watercolours. The palette is predominantly a range of warm greys, with one or two bright colours picked out as highlights. In the first half of the book, these bright colours are lively, but as the story progresses, the highlights become increasingly sanguine. Given the subject matter of the book, much care and attention is given to drawing werewolves in various stages of transformation, in styles ranging from portraits of Alice’s new “friends” (and an amazing double self-portrait) to anatomical studies of werewolf hands, feet, jaws and the like. Although Haller (or should I say Alice?) has drawn some of the most ferally gorgeous werewolves I’ve seen, her portraits of humans are stunning. As with the writing, so much of Werewolves‘ art is about conveying a mood rather than action, and there are some real successes – the drawings of those kids snarling and grinning in their hoodies, for instance, or an achingly sweet image of Alice and Mark’s mother.

I have just one complaint about Werewolves, and I’m laying the issue at the feet of the book’s designers, Kasey Free and Katie Stahnke (if you don’t know what the word “kerning” means, you can skip this paragraph). The journal entries are set in a clumsy handwriting font with perfectly regular leading. The writing style and illustrations are organic, but the machinelike regularity of the lettering goes a long way towards trashing the verisimilitude so carefully crafted by the words and images. I appreciate that books have to be produced on a timeline and under budgetary constraints, but seriously, Chronicle Books, you should have allocated the funds to get this thing hand-lettered. Design nerd rant: over.

Werewolves came out over a year ago, and I’ve been in love with it for nearly as long. It’s a nearly-perfect blend of emotionally authentic teenage anxieties and chaotic scenes of lycanthropic carnage. I highly recommend you pick up a copy – Amazon has it for stupid cheap at the moment. Read it a dozen times and you’ll still find yourself leafing through it to admire a passage or drawing. I certainly did – that’s why it took me a year to finally write this review!

Full Moon Features: 70 Years of The Wolf Man

On December 12, 1941, a horror legend was born, and it couldn’t have come at a better time for Universal Studios, which had ruled the roost in the first half of the ’30s with such iconic monster movies as Dracula, Frankenstein, The Mummy and The Invisible Man. It wasn’t until the success of 1935’s Bride of Frankenstein, though, that the studio caught the sequel bug, resulting in the production of Dracula’s Daughter, Son of Frankenstein, The Mummy’s Hand and The Invisible Man Returns — films that may have looked good in the ledger books, but lacked the spark of originality that a wholly new monster would create. Enter Curt Siodmak.

Along with his brother Robert, Curt Siodmak had been part of the mass exodus of talent from the German film industry during the ’30s, and the fact that they ultimately landed in Hollywood was no accident. Robert found steady work as a director, most notably on some of the signature noir films of the ’40s, but Curt primarily earned his keep as a screenwriter, getting his start in horror with 1940’s The Invisible Man Returns, which he tailored to Vincent Price’s talents, and a pair of films for Boris Karloff — Black Friday and The Ape. It was with The Wolf Man the following year, however, that he struck pay dirt, creating the iconic character of reluctant lycanthrope Larry Talbot and inventing much of the mythology that comes to mind when people think of werewolves today.

For the benefit of audiences who weren’t up on their werewolf lore (after all, Universal’s previous man-beast yarn, 1935’s Werewolf of London, had pointedly failed to become a hit), The Wolf Man helpfully opens with an encyclopedia entry on lycanthropy (or “werewolfism”) before establishing the “backwards” old-world locale where such superstitions are still whispered about in earnest. We’re then introduced to the unmistakably American Larry Talbot (Lon Chaney, Jr. in his defining role), the prodigal son and heir to Talbot Castle who has been away in America for 18 years and only returns after his older brother has been killed in a hunting accident. Chaney’s father (Claude Rains), a noted astronomer with a rigidly scientific mind, encourages him to get to know the people of the town, but the only one Chaney wants to make time with is antiques shop proprietress Evelyn Ankers, who just so happens to be engaged to Rains’s pipe-smoking gamekeeper (Patric Knowles). That, however, doesn’t prevent Chaney from pressing his suit and taking Ankers to visit the gypsies who have rolled into town to tell people’s fortunes.

At the gypsy camp they meet Bela (Bela Lugosi), the afflicted son of old gypsy woman Maleva (Maria Ouspenskaya), who sees tragedy looming but has no way of preventing it. In short order, Chaney kills Lugosi while he’s in wolf form, but Chaney is bitten in the process and becomes the prime suspect when Lugosi’s body (returned to human form and also with clothing on, but strangely no shoes) is discovered along with Chaney’s recently purchased wolf-headed walking stick. The curious thing about the murder investigation is the way the chief constable (Ralph Bellamy, another pipe smoker) actually leaves the murder weapon behind when he questions Chaney. Bellamy is also saddled with a bumbling assistant named Twiddle (Forrester Harvey), who provides the excruciating comic relief. One can only assume this character was foisted upon Curt Siodmak and producer/director George Waggner. After all, the Universal horror films of the ’30s had their over-the-top characters — why not this one, too?

Anyway, it takes a while for Chaney to come to terms with what he’s become (thanks to Jack Pierce’s incredible makeup job), reconciling his supernatural plight with his rational mind. (He also has to figure out how he can sit down in a chair in an undershirt, transform into a wolf man, and then be wearing a dark, long-sleeved shirt without having had time to put one on — or the dexterity necessary to do up the buttons.) And he isn’t helped much by his skeptical father, who dismisses lycanthropy as “a variety of schizophrenia” and refuses to send Chaney away despite his doctor’s recommendation. The sad thing is Rains has to lose both of his sons before he is able to accept that there are some things that can’t be explained away by science and reason. The look of devastation on his face at the end of the film tells the whole story.

It didn’t take long for Universal to realize it had a major hit on its hands. (I’ve often wondered whether its release less than a week after the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the subsequent declaration of war helped propel audience into The Wolf Man’s escapist fantasy set in a Europe completely untouched by military conflict.) Eager to capitalize on it, and prove that you can’t keep a good (or even a conflicted) werewolf down, the studio resurrected Larry Talbot two years later — with the help of Curt Siodmak, now their go-to monster man — for Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man. After 1942’s The Ghost of Frankenstein, it was clear that Frankenstein’s Monster needed a playmate if it was going to continue to be a viable property. This led to further monster match-ups with Dracula and others in House of Frankenstein and House of Dracula, until the end of the line was reached in 1948’s Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, which rather surprisingly managed to be more respectful to all three of them than either of the House films had been.

After that, six decades went by — and countless werewolves loped across movie screens — before Lawrence Talbot’s tragic story was revived with Universal’s 2010 remake The Wolfman (which has once been slated to be its 2008 remake, and then its 2009 remake). But that, my fine, furry friends, is a story for another time. For now, in this festive holiday season, take a moment to let out a howl for the most famous wolf man of all.

Full Moon Features: The Howling series, Part Two

When last we left the Howling series, director Phillipe Mora had just made a complete hash of the first sequel, 1985’s Howling II: Your Sister Is a Werewolf, yet somehow felt qualified to take a crack at another one. How he was able to convince novelist Gary Brandner that he was the man for the job I have no idea, but once he had secured the sequel rights Mora set about writing a script that had no connection whatsoever to the earlier films and, in fact, took place in Australia, the land of kangaroos, koala bears and a once-thriving exploitation film industry (lovingly eulogized in the 2008 documentary Not Quite Hollywood). And that, for better or worse, is how 1987’s mind-bogglingly bizarre Howling III: The Marsupials came to be.

I knew going into it that Howling III wasn’t exactly going to be a work of high art. (As one of the interview subjects in Not Quite Hollywood put it, “We all knew it was rubbish. We knew everything was a joke.”) In this regard, it helps that Mora always intended it to be a comedy, as evidenced by the over-the-top characters and dialogue, but that still doesn’t excuse how slapdash the whole enterprise feels pretty much from the word dingo. And even if there are no actual dingoes in the film, its lycanthropes are descended from an extinct species of Tasmanian wolf, which explains why they have pouches. (Unsurprisingly, this is the only Howling film where this is the case.)

In an odd way, the film suffers from an overabundance of ideas. For starters, there’s the story of a rebellious young werewolf (Imogen Annesley) who leaves her tribe and resettles in Sydney, where she almost immediately meets an ambitious assistant director (Leigh Biolos) who casts her in a horror film called Shape Shifters, Part 8 (a joke that the series has actually caught up with thanks to this year’s The Howling: Reborn). To this, Mora adds a subplot about a Russian ballerina (Dasha Blahova) who defects to Australia in order to find her werewolf mate. (Her transformation in the middle of a rehearsal provides one of the film’s highlights.) Then there’s the college professor (Barry Otto) who’s eager to study the creatures and eventually develops something of an affinity for them. If only people could understand them, he believes, we wouldn’t be so afraid of them.

Even if the whole thing falls apart well before the climax (at a tacky-looking awards show hosted by Dame Edna Everage, of all people), Howling III is almost worth seeing for the early scene where Biolos takes Annesley to her first horror film (she’s lived a sheltered life in her remote hometown of Flow — yes, that is “Wolf” backwards) and she is decidedly unimpressed by the lengthy transformation sequence. Of course, since it was done for the movie within the movie, Mora and his crew deliberately set out to make it look as ridiculous as possible, which is not a claim that the makers of the next sequel can make — at least, not credibly.

Having reached a narrative dead end in the Australian outback, the Howling series was given a pointless reboot with 1988’s Howling IV: The Original Nightmare, which harkened back to Gary Brandner’s source novel. Actually, according to the opening credits, it’s based on all three of the Howling books, but for the most part the screenwriters stick to the story of the first one, save for the fact that the main character is no longer the victim of a savage rape. Instead, Marie (Romy Windsor) is a bestselling novelist who’s having such disturbing dreams and visions that her doctor prescribes a liberal dose of rest and relaxation. This prompts her bearded husband Richard (Michael T. Weiss) to rent a rustic cabin up in the mountains so she can get away from the big, bad city, but the peace and quiet is shattered their first night there when Marie hears a wolf howling nearby and stupidly asks, “What was that noise?” (Just once I’d like a character to hear a wolf howl in a movie and immediately know what it is.)

To his credit, director John Hough manages to bring a sense a menace to the scenes that take place in the nearby town of Drago, but his efforts are hampered somewhat by the barely passable American accents on most of the townspeople (not much of a surprise considering the film was shot in South Africa). This problem also extends to Marie’s agent, who mostly exists so Richard can have someone to be jealous of after he’s been seduced and bitten by she-wolf Eleanor (Lamya Derval), an artist who runs the local knickknack shop. The other major character is an ex-nun named Janice (Susanne Severeid) who helps Marie investigate the strange goings on in town, but their sleuthing skills are amateurish at best. In fact, it takes them so long to put things together that nearly an hour elapses before somebody says the word “werewolf” — and that’s a hell of a long time to keep your monster off-screen.

Then again, that was probably entirely by design because the werewolves in Howling IV are pretty pathetic. The main problem appears to be the makeup department’s inability to pick one design and run with it. Instead, there are at least half a dozen werewolf concepts ranging from ordinary wolves with glowing red eyes to an upright wolf man on two legs. Then there’s the matter of Richard’s ludicrous transformation, during which he dissolves into a puddle of goo and then reforms as a wolf-like thing. Meanwhile, all the other werewolves just sort of tease their hair out and glue on fangs and claws so they can swipe at Marie when she attempts to escape their clutches. It’s all pretty half-assed, which is why it’s not too surprising that the filmmakers can’t even be bothered to stick a proper ending on the thing.

Given its tiny budget and poor production values, it’s not surprising that Howling IV was the first sequel to go direct to video. And it was soon joined on the shelves by the likes of Howling V: The Rebirth (1989), Howling VI: The Freaks (1991) and Howling: New Moon Rising (1995). The last one even tried to tie together the events of the previous three, and topped Howling III‘s marsupial werewolves by adding line dancing into the mix. More an act of desperation than a legitimate film, New Moon Rising sounded the death knell for a series that had been thoroughly run into the ground in the space of a decade and a half. No wonder it took just as long before the time was ripe for it to be Reborn. (The fact that a little something called Twilight came out in the interim may have something to do with that, but that’s a discussion for another time.)